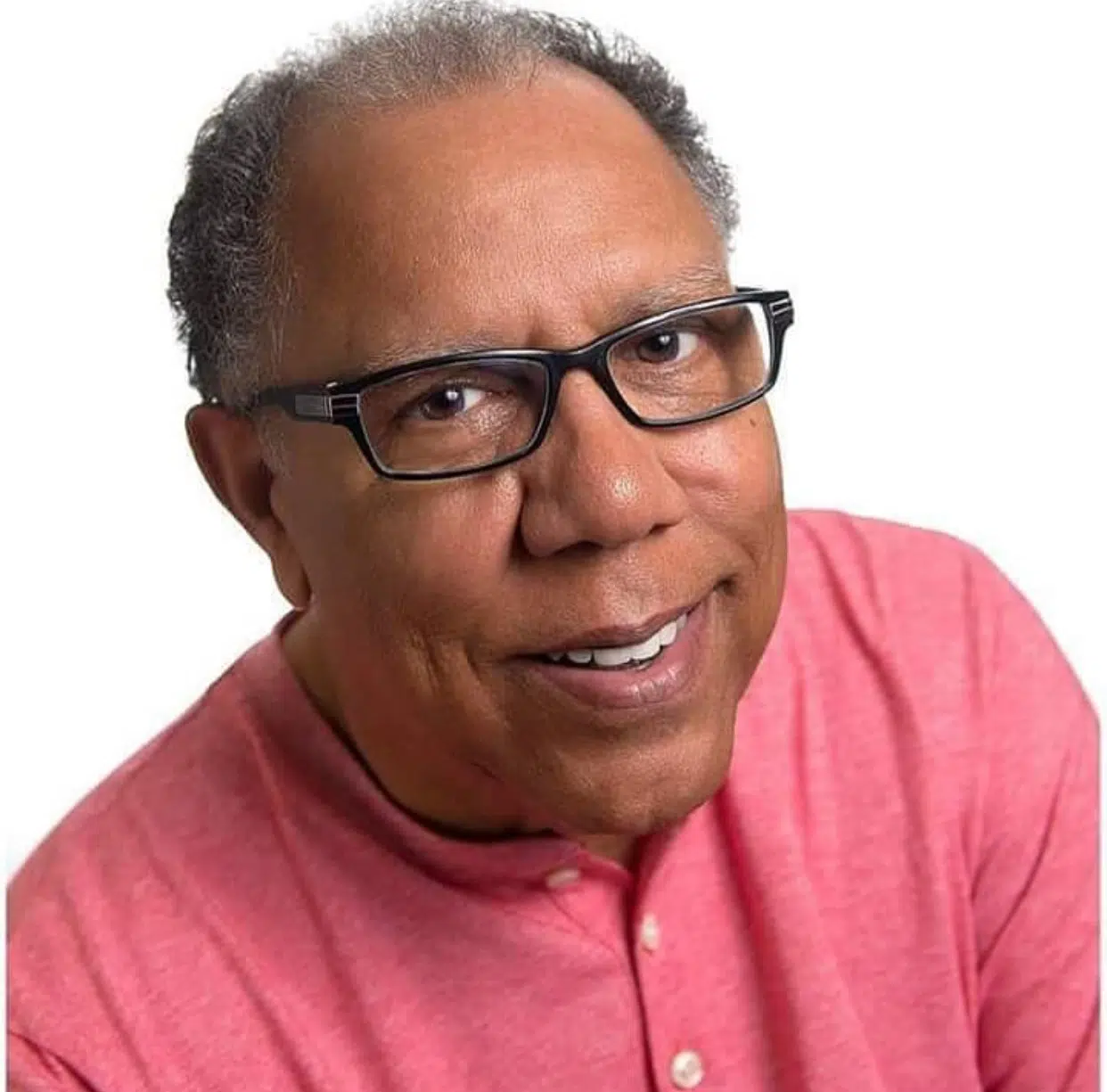

The NC Central basketball coach explains why he’ll always “speak up for those who may not have a voice.”

Like most of the world, the killing of George Floyd affected North Carolina Central men’s basketball coach LeVelle Moton; and, yet, unlike many, Moton could relate to the police brutality aspect to a degree that “triggered my anxiety issue.”

In 2005, while driving with then North Carolina men’s basketball star Raymond Felton, Moton said he was pulled over, “snatched” out of his truck and had a gun pointed at his head by police in Raleigh, N.C.

“Obviously, I was terrified,” Moton said. “They never went over protocol. They never asked for license and registration. They never even realized Ray was in the truck.”

Despite it being a rainy night and Moton having tinted windows on his truck, the police officers told him he “fit the description.” Moton’s saving grace?

A backup officer arrived and recognized him. Then, when they finally saw Felton on the passenger’s side, the officers knew they’d made a mistake.

Roughly 30 days prior, Felton had led the Tar Heels to the national title, an 87–71 win over Illinois.“I was humiliated,” Moton said. “It was the first time that I felt like less than a man … I thought I was going to be killed.”

Floyd, a Black man, died on May 25 after being pinned beneath police officers, one of whom kneeled on his neck for eight minutes and 46 seconds, as he was detained. Floyd repeatedly told the officers that he couldn’t breathe.The officer who kneeled, Derek Chauvin, was later fired, arrested and charged with second-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter; the other three officers—Thomas Lane, J. Alexander Kueng and Tou Thao—were charged with aiding and abetting second-degree murder.

Moton was the first coach to come out and challenge white Power 5 coaches to speak out in the aftermath, many of whom have since made strong statements against social injustice and police brutality.

“The way I looked at it, that was progression within itself,” Moton said of coaches speaking out. “It’s predicated off of love, but in those initial times I just felt like we all needed to stand up for people with the complexion of George Floyd and be there for those student-athletes that we coach in the same manner that they’ve been there for us. The truth is I’ve lived in poverty over half of my life, so I can always and will always directly relate to people of those backgrounds. They need a voice. That’s what I’ve always done my entire life is speak up for those who may not have a voice.”