By Carter Dewees

For The Birmingham Times

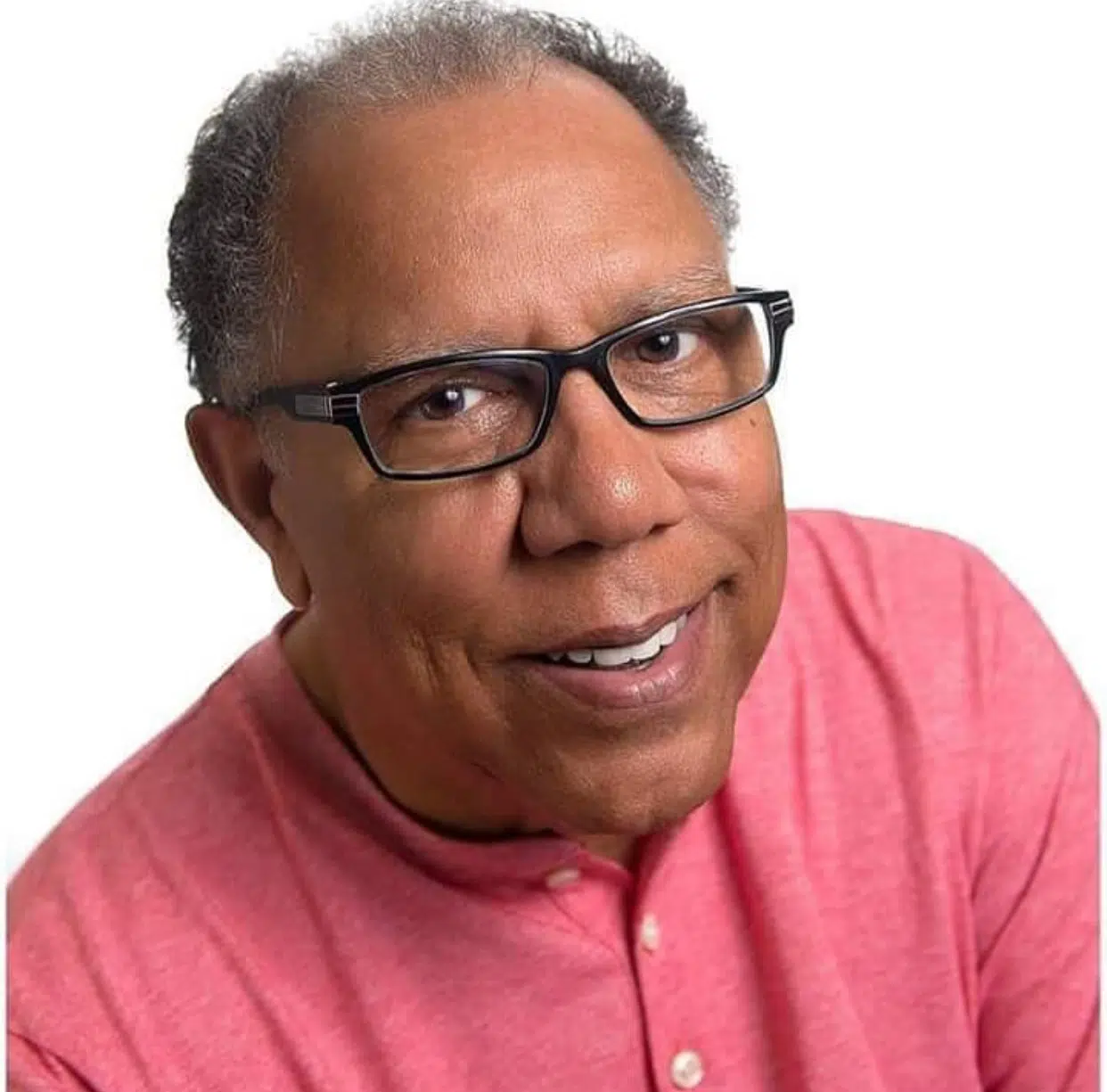

Growing up as the youngest of six siblings in Birmingham’s Collegeville community, Derrick Ervin had one hero—his dad.

“He would wake up at two in the morning and [after work] be back in the community by six in the evening to organize a team-sports event,” said Ervin.

His father was his “Superman,” an important figure in Collegeville community and the representation of what manhood meant to Ervin. He would watch his dad get up in the early hours of the morning to drive a truck and return later in the day to coach and mentor children. When his dad died abruptly, Ervin was 10, and he had a difficult time squaring the death of his father with his belief in God.

“That was when I started turning to the dark side,” said Ervin, noting that his father’s death left him feeling broken and overtaken.

Then, when Ervin was 21, his mother died of a brain tumor.

Ervin, who turned 50 in May, said he was a broken child, with old wounds from his father’s passing that had not been healed: “That’s when I began hating God because I felt like I had prayed death upon her.”

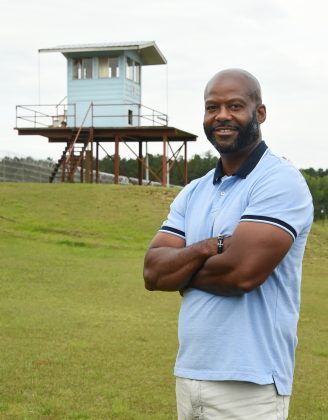

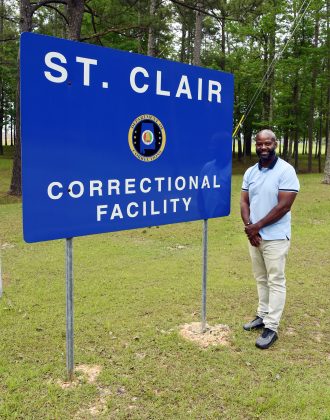

This was the turning point for Ervin, who embarked on a life of a drug dealing and received a life-without-parole sentence, which he would serve at the St. Clair Correctional Facility in Springville, Alabama.

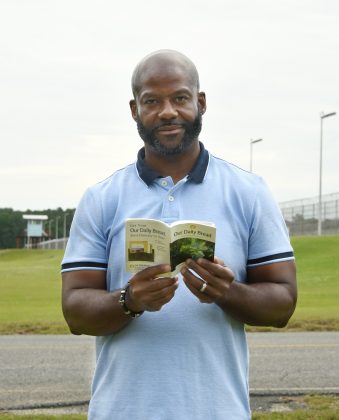

There, Ervin, who had begun serving his sentence just over 13 years ago, discovered and embraced the Prison Fellowship Academy, a nonprofit program dedicated to embracing and rehabilitating inmates at prisons, primarily through the discovery and nourishment of their faith—and it saved his life, he said.

“It wasn’t the state of Alabama that arrested me,” said Ervin. “My favorite saying is ‘God arrested me.’”

In August 2019, Ervin’s sentence was altered to include parole, and he was released slightly more than a year later. Today, he serves God as a member of the Prison Fellowship, so others may be saved from the darkness that he knows too well.

The Prison Fellowship sends chaplains to prisons across Alabama to help with ministry through Academies, such as the one at St. Clair, where Ervin did his time. After Ervin got involved in the program, it forced him to “take a deeper look” within himself and “define what manhood is.”

When in prison, men often lose hope, Ervin said. In many cases, no family members visit, and the prison might feel like an island. Even though he faced many hardships, Ervin found hope through prison ministry.

Hope and Restoration

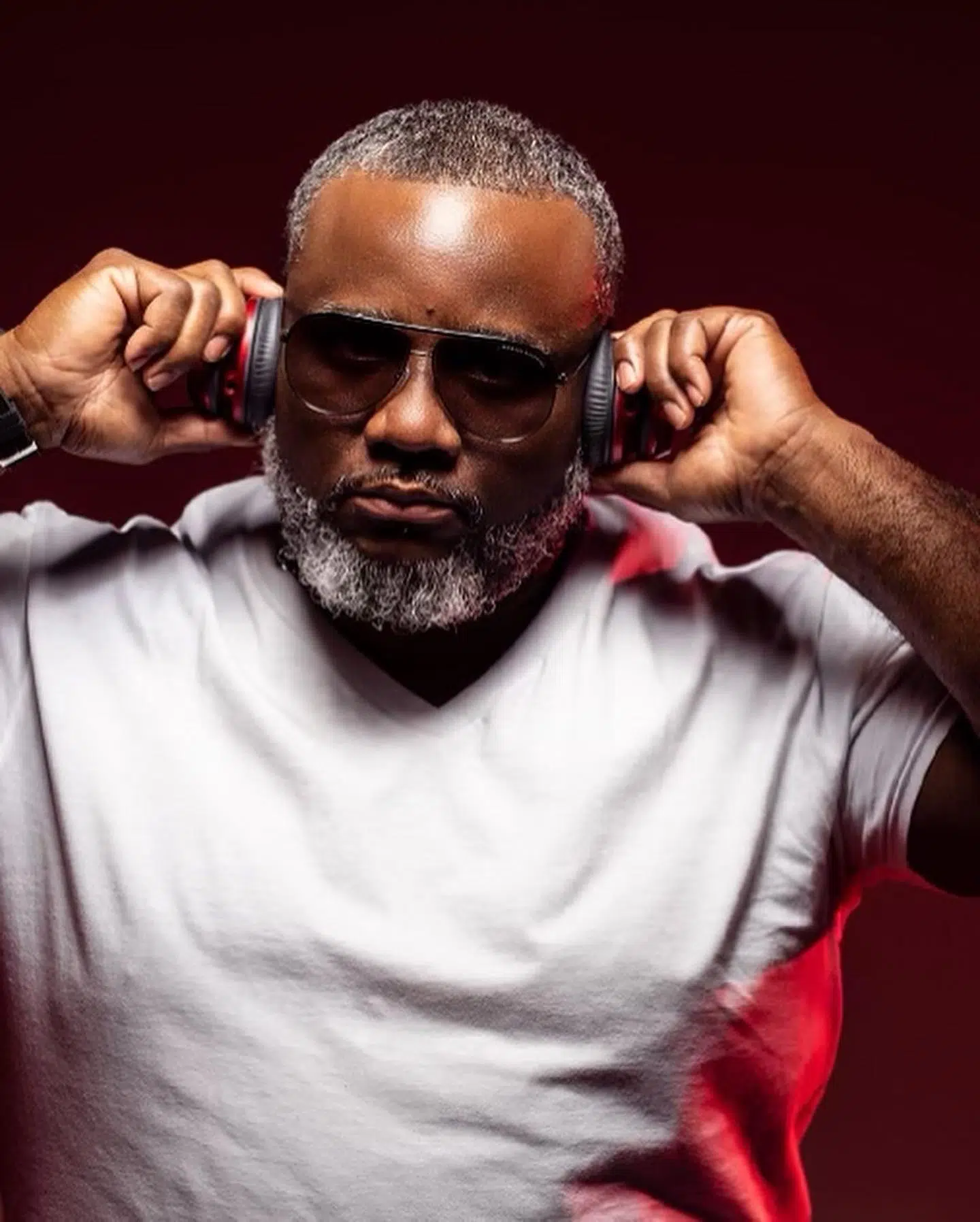

Jeremy Miller, who worked as a chaplain for the We Care program, formed a friendship with Ervin at the St. Clair Correctional Facility.

“I first met [Ervin] when I was an assistant chaplain at [St. Clair] back in 2013,” said Miller. “He has always had an intent to do what was right. When I met him, he was working to help people get their GED, and he had a servant’s heart. He served as a hospice worker, a chapel worker. … He always had a servant’s heart, but he was always a leader—and a leader for change.”

Miller said Ervin was the guy that people looked up to: “He never got in trouble and always tried to help and bring peace and resolve conflict. He was a guy that knew where he stood with God and had an intense desire to follow God’s calling on his life.”

For many men behind bars, the Prison Fellowship program and its ministry represent a better future and a chance to make wrongs right.

“Prison Fellowship admitted me as a family,” Ervin said. “To me, it means hope, restoration, and reconciliation.”

The Prison Fellowship Academy involves individuals from outside the prison visiting inmates weekly, which Ervin said had a big impact because it makes inmates think, “I have somebody out there who’s willing to come here, sit in this class with me, and not just teach me but pray with me. I can do better.”

When the Academy at the St. Clair Correctional Facility started in 2019, Miller said he wanted Ervin to be a part “because he was that leader.”

“I knew that if there was to be success in St. Clair, then we needed good peer leaders like [Ervin] to stand up. He was a good leader in the prison,” Miller said. “I think going through the Academy [enabled Ervin] to build relationships with people, and he was able to pull people into our programming because he had those relationships.”

Ervin recalled that the Academy affected day-to-day life for him and his fellow inmates, even when they chaplains were not present.

“We began to hold each other accountable, right there behind prison walls, to be men of standard,” said Ervin. “The concepts of accountability, fellowship, and brotherhood form a beacon of hope in a difficult setting.”

Ervin, who would go on to serve as a chapel worker under Miller, was released on Oct. 7, 2020. He now helps Miller, who is now the Alabama field director for Prison Fellowship, with events around the state. For Ervin, it’s his way of giving back to the program that has given him so much.

“Faith without works is dead, so it’s my work,” said Ervin, who serves as essentially the sole stage provider for the program in Alabama, traveling to meet the needs of the ministry.

Giving Back

Ervin is a North Birmingham native, who hails from a large family that still lives in the area. He graduated from G.W. Carver High School near the top of his class and was an exceptional athlete. He went on to attend North Carolina State University on a full football scholarship to play defensive back, but moving nearly 1,000 miles away from his family and his mother brought its own problems.

“I had all this hurt alone, and I didn’t have an answer for it,” he said. “I took all this baggage 800 miles away.”

Later Ervin transferred to the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga before returning to Birmingham when his mother was diagnosed with a fatal brain tumor.

Following his mother’s death, Ervin worked many jobs, including one with an avionics technology company at the Birmingham-Shuttlesworth International Airport, and one through which he played a key role in building a gas station that still stands. Ervin was in the convenience store business for more than a decade before his conviction and was trained both in income tax preparation and as a licensed home builder.

His mother’s death was a turning point that led to Ervin’s transformation from a college athlete into a drug dealer. He lived a double life, with his wife, Shemelia, unknowing of his involvement in the drug trade.

“She was always a Christian, and she didn’t know she was sleeping with the devil at the time,” he said.

For Ervin, manhood meant providing for his family, no matter the consequences. He became involved in businesses with his acquired wealth throughout the South and in Texas, where he owned a nightclub. Eventually, Ervin met his reckoning when he was convicted for drug trafficking and sentenced to life without parole at the St. Clair Correctional Facility.

“There Is Hope”

When Ervin was released in 2020, he put this unique skill set to use. He studied civil engineering in college, but his mind had always been geared toward business.

Civil engineering gave him an edge, though, Ervin said. After college, he had the opportunity to work with an avionics technology company, AMR Combs, which is a subsidiary of American Airlines. He also owns property on the corner of Arkadelphia Road and Third Avenue West in Birmingham, where he built a gas station. Additionally, Ervin and his wife—who will celebrate their 27th anniversary on July 9 and have two sons, D.J. and Devin—have owned a cleaning business since 2004 which Shemelia grew while her husband was incarcerated.

The business, Cleaning Concepts Plus, LLC, has contracts in 37 different states. The Ervins give back through their business, hiring ex-convicts so they have the opportunity to work and provide for their families. Ervin said some of his past wounds have been healed by learning from Jesus, who he says is the perfect example of a son.

“I allowed Jesus to teach me because I never failed as a man, and I never failed as a father. I failed as a son,” he said.

Since his conviction, Ervin has learned what it means to be a man and a man of God. When he got to prison, he said, “I realized that I had to be healed. If the hurt little child was never healed, the true man could never grow.”

Ervin said that God has taken him from behind the walls to do His work on the outside. He describes his path to restoration as an “open door” that he walked through to a better life.

When Ervin speaks with inmates, it’s important to share that “there is hope [for] men behind iron walls—and that hope is in Christ,” he said.

How the Prison Fellowship Academy Works

The Prison Fellowship Academy is a nonprofit program dedicated to embracing and rehabilitating inmates at prisons, primarily through the discovery and nourishment of their faith.

In 1976, Charles “Chuck” Colson, who was Special Counsel to President Richard Nixon from 1969 to 1970 and served time Alabama’s Maxwell Prison for a Watergate-related crime, founded Prison Fellowship, which is now the nation’s largest Christian nonprofit organization supporting prisoners, former prisoners, and their families. The group is a leading advocate for criminal justice reform.

Jeremy Miller, Alabama field director for Prison Fellowship, explains the goal of the Academy initiative.

“Our goal is to have men and women who come through our Academy see life differently, deal with the things that caused them to go to prison, and then see life differently—and see it through a Christian worldview,” he said. “The Academy has another factor, too, [in that] people who go through the [program] have success and it is life changing for them. When they go through the Academy and are able to deal with the thought patterns and the things that caused them to go to prison, then they are able to also work through those issues in a community [setting] that involves small groups. … We actually go through a curriculum and then have small groups, through which [participants] are able to build community.

“Our goal is to have them turn into change agents to help see change happen inside the prison. Then, when they are released, they have an impact on society, as well.”

To learn more about Prison Fellowship, visit www.prisonfellowship.org or call 800-206-9764.