Months before Jordan began his NBA career, he auditioned for a spot on the 1984 U.S. Olympic Team. Writer Jon Wertheim got to experience it as a 13-year-old from Indiana.

Our sports drought is over. Sort of. ESPN will debut the multi-part, mega-anticipated Michael Jordan documentary Sunday night.

Months before Jordan began his NBA career, he—along with 71 other American players—auditioned for a spot on the 1984 U.S. Olympic Team. A dispatch from the event, adapted from the forthcoming book “Glory Days: the Summer of 1984 and 90 Days That Changed Sports” by L. Jon Wertheim.

—

It was as if the circus had come to town. Only the attractions weren’t animals, clowns and tightrope walkers but, rather, abnormally tall men in their early 20s. In the spring of 1984, Bob Knight was tasked with putting together the roster of the U.S. men’s basketball team he was going to coach in the Los Angeles Olympics. So he invited six dozen of the top amateur players to the site of his kingdom and my hometown—Bloomington, Ind.—for auditions.

As Karl Malone, then a burly forward at Louisiana Tech, put it to SI at the time, “They said they was gettin’ the best 72 and they wasn’t tellin’ no stories.” Malone wouldn’t survive the cuts.

In keeping with Knight’s sensibilities, the players were not exactly coddled. Joe Kleine, then a forward from Arkansas, recalled flying into Indianapolis—you went to Knight; he didn’t go to you—and getting the no-frills treatment as soon as he landed. “We all picked up our own bags and then piled into these buses. It was like going to Camp Wong-a-Monga or whatever. Except you’d look around the bus, and it was Michael Jordan across the aisle and Charles Barkley in the row behind you and Patrick Ewing in the row ahead of you.”

Those auditioning lodged in rooms at the Indiana University Student Union and ate in the cafeteria. They were transported around town in maroon vans, three players per row. The try-outs were held not at the venerable Assembly Hall but at the IU Fieldhouse, a no-frills gym smelling of Bengay and an indifference to showering. There was no hospitality, no security detail, no hangers-on. When practice was over, the players were on their own, ambling around town, sometimes accepting rides to the movies from strangers.

For a 13-year-old incurable basketball junkie, this was a hell of a speedball. After school, I would peddle my bike a mile or so to the Student Union and observe/accost the same players I’d been watching on TV a few months earlier. I stood back and watched then 285-lb. Charles Barkley put on an awe-inspiring eating display. I played video games with Wayman Tisdale and pool against Chris Mullin. They seemed happy for the company.

To a man, the players were exceptionally cool, uncorrupted by fame/money and giddy about the Olympics and, more generally, their bright futures. It was like a continuation of college life, just on a different campus.

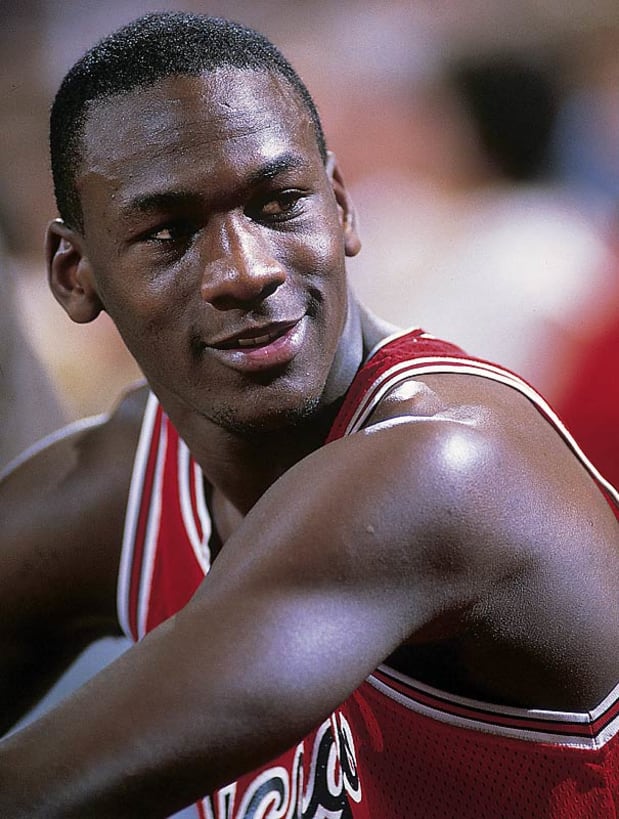

Even so, one player had a different level of magnetism and charisma. Wearing Bermuda shorts, collared shirts and a permanent smile, Michael Jordan walked around with a braying confidence that suggested he knew what successes awaited. He had agonized over his decision to leave UNC and go pro. He wanted to stay. So did his mom. It was his father and his coach, Dean Smith, who wanted him to go to the NBA, earn an honest living, and eliminate the risk of a fluke injury while an unpaid college player.

In Bloomington, Jordan joked easily in a deep voice and dispensed nicknames. One day, he spotted me carrying a tennis racket. “Hey John McEnroe!” he said, miming tennis strokes. “When are we gonna play?” Around town, his autograph didn’t carry much currency, as supply kept pace with demand.

Jordan was popular among his new teammates. He got along especially well with the lone black assistant coach, George Raveling. He listened intently while Raveling talked about being on stage for Martin Luther King’s “I Have. Dream Speech.” He rolled his eyes when Raveling tried to convince Jordan to shod himself in Nikes, not the Adidas shoes Jordan, accountably, preferred to wear.

Jordan even had a soft spot for Knight. He was shocked by the coach’s language. “I learned the four-corner offense from Coach Smith; I learned the four-letter word from Coach Knight,” Jordan joked more than once. But he could relate to Knight’s abiding drive for perfection.

Of course, Jordan could play a little too. He’d just finished his third season at North Carolina—ironically, losing to Indiana in his final college game—and was pegged as a high lottery pick. At the Olympic trials, his aura grew, as he distanced himself from the others. My friend and classmate, Pat Knight, the coach’s son, regaled the seventh grade kaffeeklatsch with stories of Jordan’s feats during practices.

Bob Knight gushed uncharacteristically about his shooting guard and warned that any NBA team foolish enough to pass up drafting Jordan would regret the decision. “Jordan’s game is made for the NBA,” he declared.

The Portland Trail Blazers held the second pick in the 1984 NBA Draft. It was an open secret that the Houston Rockets would take Akeem—the H in his first came later—with the top pick. But Knight urged Portland’s general manager, Stu Inman, to take Jordan first.

“We need a center,” Inman said.

“S—,” Knight said, “take Jordan and play him at center.”

The Blazers, of course, picked Kentucky center Sam Bowie, leaving the Bulls to swoop up Jordan with the third pick.

Knight wasn’t entirely prescient that summer; the players he cut from his team included Malone, Barkley, John Stockton and Joe Dumars. But he sure had Jordan pegged.

Jordan breezed through the various rounds of cuts as the roster was winnowed to 12 players and two alternates. The team was now practicing at Assembly Hall and, hoping to catch Jordan in action, a few of us hatched an elaborate plot to sneak into a team practice.

It was totally unnecessary. We simply walked into the gym through an unlocked door and sat in the bleachers. At one point, Jordan blew by four men, including Ewing, and threw down a dunk. Even Knight let loose an admiring whistle that pierced the air. That afternoon, I saw Jordan, alone, at his favorite haunt in Bloomington, the Chocolate Moose ice cream shop. I told him what I’d seen. “You know what, John McEnroe,” he said, “that wasn’t even my best dunk.”

Jordan was the third pick in the NBA draft that summer. A few weeks later, he led the U.S. team to the gold medal. And then he really blew up. In the retelling of the Jordan Narrative, he didn’t officially arrive until he led to the Bulls to a title in 1991. In truth, a few months into his rookie season, he’d already cracked the Bird-Magic duopoly.

The NBA All-Star Game was held in Indianapolis that season and, still another stroke of good luck, I won tickets through some local radio give-away. Before the game I huddled with other autograph hounds near the lip of the court. When Jordan came out for warm-ups, he saw me, stopped and turned. “Hey, John McEnroe,” he said, cackling and shaking my hand. “What’s going on?” That interval—a sum total of, maybe five seconds—may well have been the highlight of my teenage years.

It would be more than 10 years before I would again see Jordan, up close and in person. In that time, he’d win three NBA titles, establish himself as an iconic figure, retire and then return. In 1996, I was writing an NBA article for an airline magazine on a prominent announcer and saw Jordan in the tunnel of an arena. I re-introduced myself and tried to jog his memory. ”John McEnroe” no longer had resonance; he did, however, fondly remember those months in Bloomington and, specifically, the ice cream at the Chocolate Moose.

Fast forward another six years. Jordan was in his late 30s, he’d won six titles, and cemented himself as the undisputed Greatest Ever. In the early winter of 2002, he was in the midst of an odd encore with the Washington Wizards. During a successful stretch, I was assigned to profile him for SI. Watching the pregame mob scene, Jordan ambushed by reporters, handlers, and hangers-on, I smiled recalling the kid who walked around Bloomington alone and unbothered in 1984. During a lull in the media frenzy I sidled over and, attempting to establish some connection, started in on a “I’m sure you don’t remember, but…” monologue.

“Michael’s not taking more questions,” a handler said stonily.

Jordan ignored him. “I remember one place had damn good ice cream,” he said, without looking up.

“Okay,” the handler said. “Michael won’t be available again until tomorrow.”